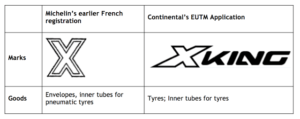

Over at the IPKat, there is a report about a CJEU decision upholding Michelin’s opposition based on its “X” trade mark to the registration of Continental’s “XKING” mark (below on the right), both in respect of tyres.

You should read the report, if for no other reason, than the revelation of the EU’s “scientific” approach to trade mark conflicts.

Putting to one side the peculiar procedural posture the CJEU seems to take in these kinds of ‘appeals’, Merpel quite rightly thunders about scope afforded to ‘descriptive’ marks. After pointing out that it has taken 5 years to get to this point, Merpel says:

The end result here is that one trader with a weakly distinctive trade mark for the single letter X, distinguished from the letter of the alphabet only by the merest stylisation, can prevent the registration (and potentially use) of a stylised mark XKING. It must also follow that the same trader can prevent other X-formative marks, especially if the other element is in some way laudatory (and the word “king” is hardly at the top of the laudatory scale). Might it be said that this hands too strong a right to the trader?

Merpel makes a cogent case for the rejection of the opposition. What I wonder about, however, is what is the ordinary consumer likely to recall imperfectly? Would the ordinary consumer recall the mark is just an “X” alone so that the inclusion in Continental’s mark of rather bland “KING” is sufficient to dispel any potential for confusion? Or is the putative consumer likely to be struck by the common use of the hollow (or white) X? Under our version of trade mark law, all that is required is a (significant?) number of people being caused to wonder and the nature of the recollection is explained by Latham CJ:[1]

They will compare the actual mark which they see upon goods which are offered to them with the memory of the other mark, which they will retain in a more or less distinct form… The court must endeavour to put itself in the position of ordinary purchasers of goods who have noticed a trade mark as being distinctive of particular goods, but who have not compared that mark with any other mark, and who are quite probably not aware of the fact that another more or less similar mark exists.

[socialpoll id=”2454828″]

If you’re really motivated, leave a comment explaining why!

- Jafferjee v Scarlett [1937] HCA 36; 57 CLR 115 at 122. ?